Peter Bellamy

Written by Caspar Santacroce.

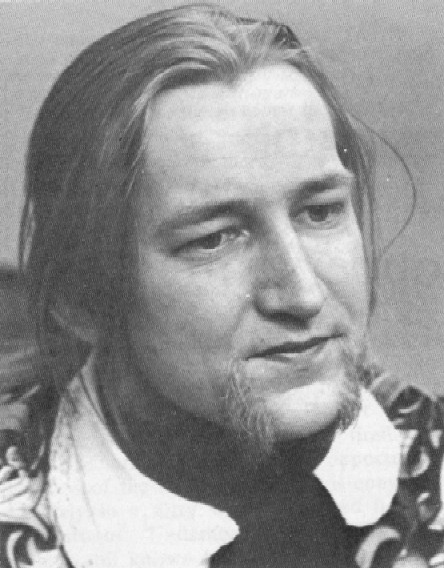

The word they use for his voice is "bleating". Born in Bournemouth, raised in Norfolk, Peter Bellamy (1944-1991) sang like it. His style is cutting, bardic, a strong old calf-like waver on the high notes and an expressive sense of personality emerging from his devotions to local folkways. One critic has said that he sang "like a master fencer with a clubfoot". A fine phrase, though fencing (clubfoot or no) is at once too upper class and too modern for Bellamy. He is more goatish than that-awkward from close up, but when you see him scaling his rocks he does it with a tough grace.

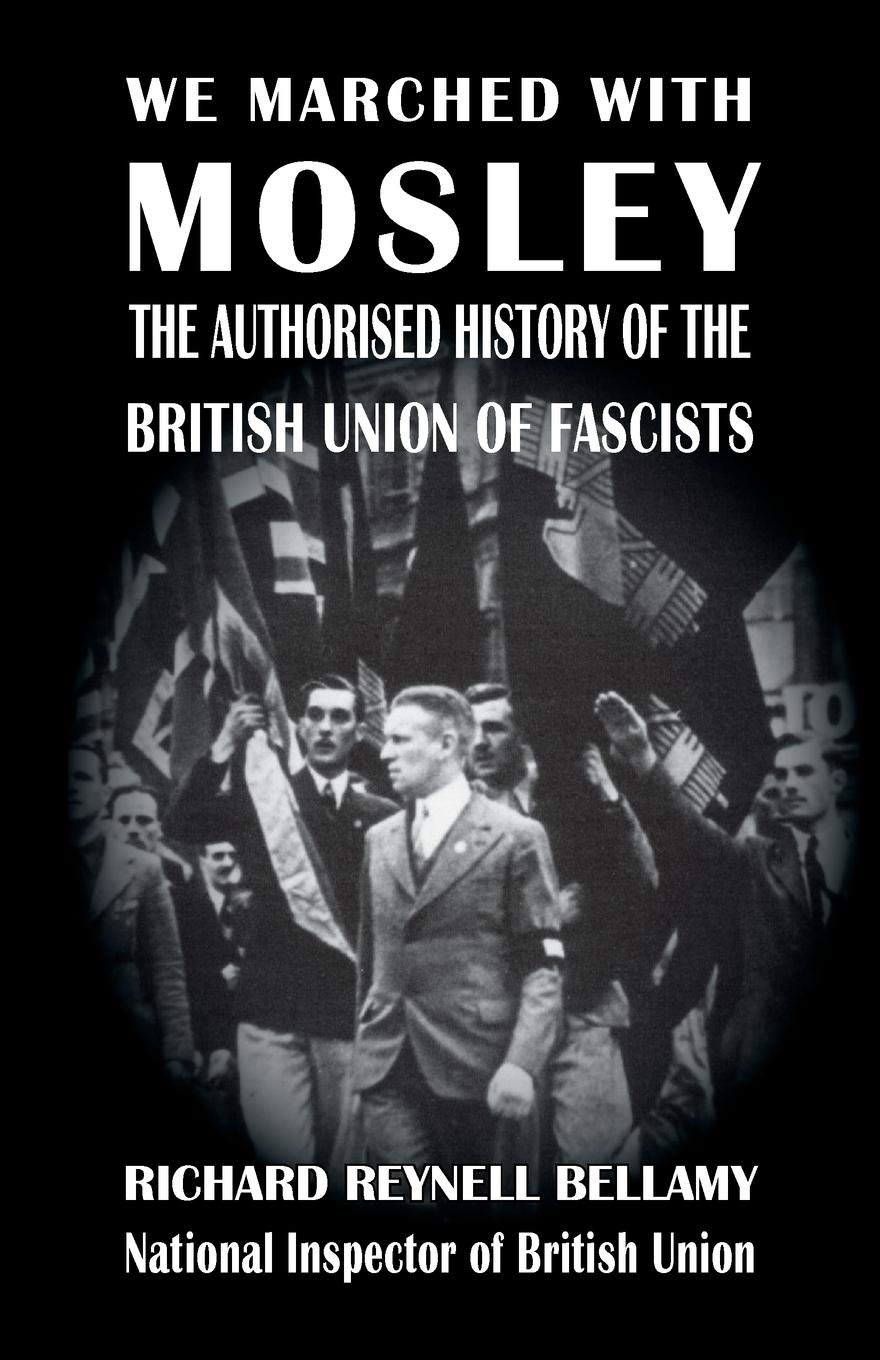

His father was a Fascist. Richard Reynall Bellamy called his memoirs We Marched with Mosley-the reference is to the disgraced Anglo-Hitlerian leader Oswald Mosley. He had assumed the ominous party role of National Inspector in the British Union of Fascists and in 1940 was sent to prison. Peter was slouching all his childhood towards art school, velvet pants, and a Warhol-esque ponytail. Did he ever think much about the prison cell his father paced a few years before he was born? He did not (fortunately for all involved) inherit his father's politics, but perhaps something of a reactionary sense of tragedy haunted him through his life. In 1991, to the shock of the folk community, he committed suicide.

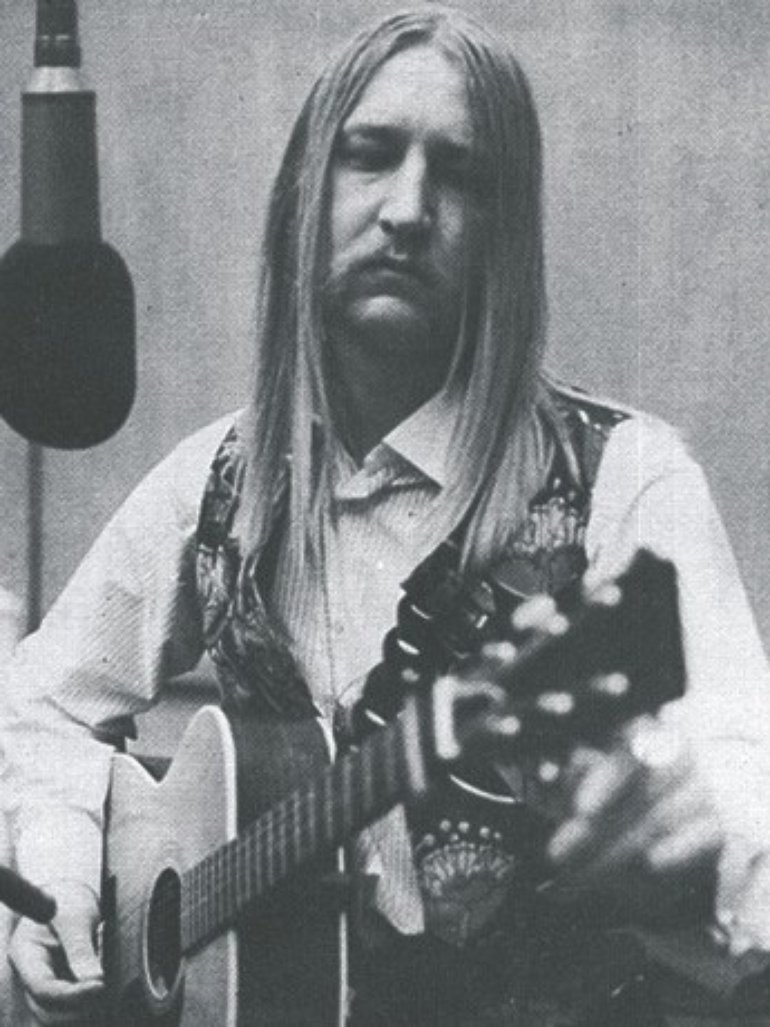

So much can be said about Bellamy's life, which so many can only see through his death at the end of it. At his death he left behind bundles of bootleg and limited recordings, and it can be hard to get a sense of just how much he recorded. Along the way, before all that, he put out solo albums (his first, in 1968, was named "Mainly Norfolk") and had a middle period as front man of folk group The Young Tradition.

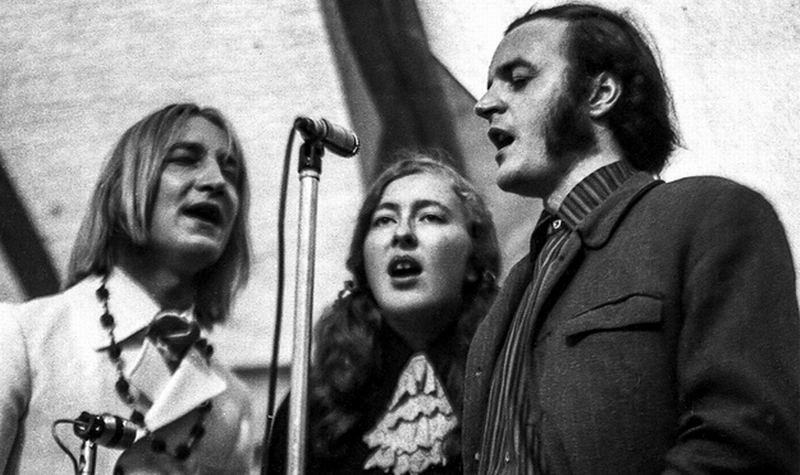

At their best the trio of the Young Tradition (Bellamy was joined by Royston Wood and Heather Wood) bring a sharp hypnotic edge to traditional English folk. The first song on their self-titled debut is "Byker Hill". They make the piece, a Newcastle ballad about coal-miners, sound like a marching song for its revolutionary and at the end strangely melancholy subjects.

Peter Bellamy (left), Heather Wood (middle), and Royston Wood (right) started The Young Tradition in April 1965.

It is that mix of warning and lament that so distinguishes the album's highlights. Bellamy and the Woods hit their most distinctive measure on "Lyke Wake Dirge". The song is medieval, a cryptic little riddle about purgatory with the ghostly refrain "Every nighte and alle, / Fire and fleet and candle-lighte, / And Christ receive thy saule". The Young Tradition's setting honors those old roots and manages to sound at the same time like some clipped Neo-English for a newly resurgent feudalism far in the future. I make the album seem gloomy, and the cover with its subdued tenebroso photo of the band and the archaic sigil up top don't help much on that front. But the album is tender (listen to "Dives and Lazarus"), gently rousing ("The Bold Fisherman"), ironic ("Pretty Nancy of Yarmouth) and just sometimes joyful too ("The Innocent Hare").

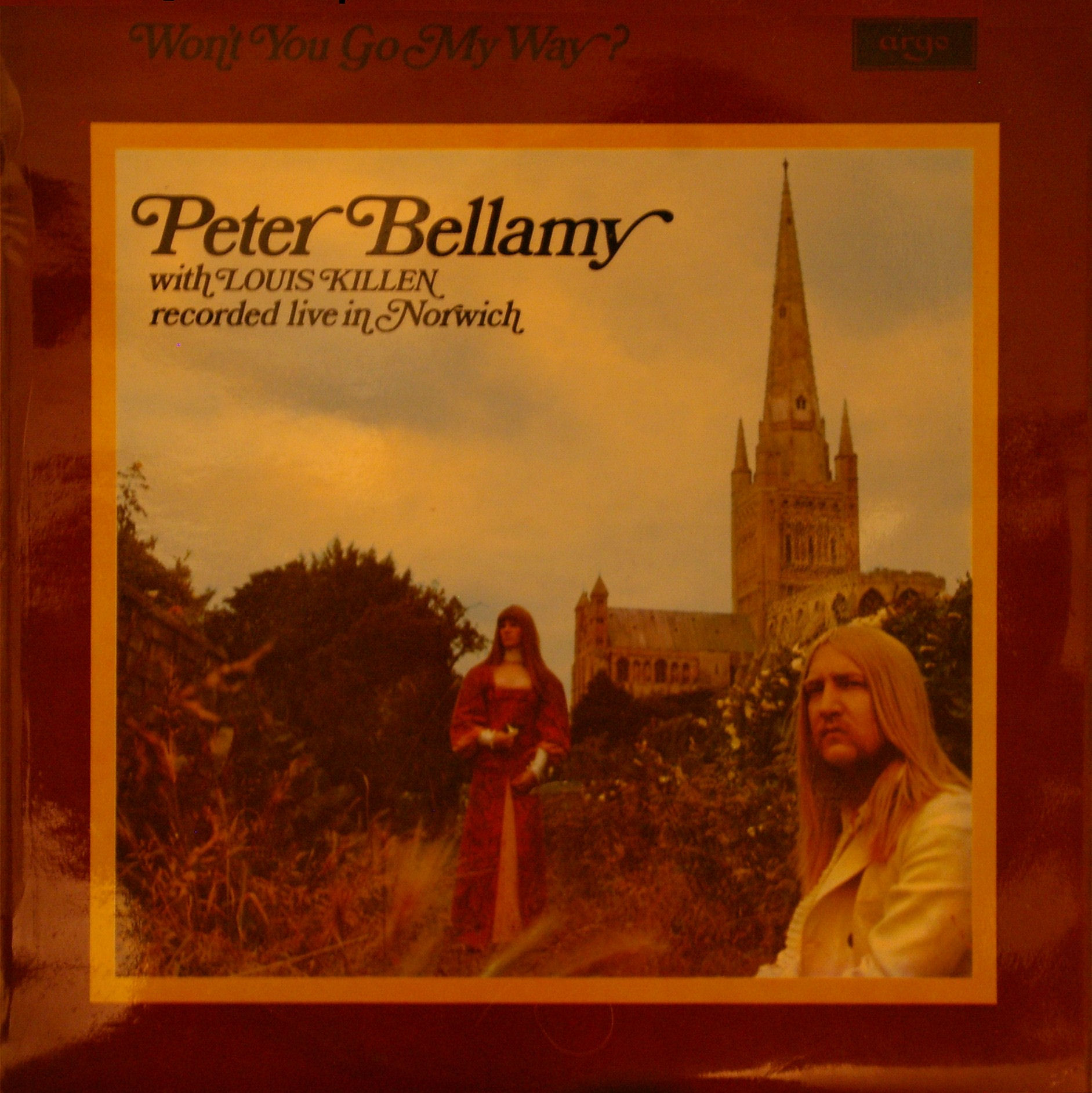

By the end of the 60's The Young Tradition split up. Bellamy continued for the next 20 years on his own peculiar way. This final stretch saw his voyage into English sea-shanties, a folk opera about working-class burglars falling in love on convict ships sent to Australia, and (most infamously) his musical settings of poems by Rudyard Kipling.

Bellamy isn't dedicated to defending Kipling so much as he is in clarifying him. In these unflinching pieces-collected across multiple albums-we hear in Bellamy's voice the flashing impedimenta of empire, but we hear something more human as well beneath. He marshals all his feeling for common speech, and Kipling's rough demotic rhythms become less chauvinistic cast into Bellamy's dignified whine. "Danny Deever", a dialogue between a private and his officer about the execution of a soldier caught stealing, unifies its speakers through Bellamy's refusal to differentiate their voices. We get a sense that the comradery of seeing summary injustice touches both men and erases, if only for the song, the hierarchy between them. Meanwhile on "Gentlemen Rankers" Bellamy commands a poem about aristocratic decline-the title refers to British members of the upper class forced out of wealth by misbehavior to enlist as a common soldier-to march along more universal cadences. When we get to certain passages we almost might feel Bellamy is speaking to us about himself:

"When the drunken comrade mutters and the great guard-lantern gutters,

And the horror of our fall is written plain,

Every secret, self-revealing on the aching whitewashed ceiling,

Do you wonder that we drug ourselves from pain?"

Almost feel, that is. Bellamy is a bit savvier than Kipling on speaking through these characters. It is the great merit of his settings that we recognize both their beauty and their brutality. In another Kipling piece about pre-Christian English seafarers, the "Song of the War-Boat", Bellamy begins bellowing over the delicate surge of the piano accompaniment:

"Hearken, Thor of the Thunder!

We are not here for a jest-

For wager, warfare, or plunder,

Or to put your power to test."

Bellamy's reluctant all-hands-on-deck attitude carries the song. It carried him too through his life on the swells of British folk. The roll and the rise of his bleating put him in troughs enough, but he also had a sense of humor about it all. A caricature of him appeared in 1980 in The Southern Rag as one "Elmer P. Bleaty", an anagram of his name. Bellamy bought a copy of the issue, cut out the page, and hung it in his living room.